Today is the seventy-fifth anniversary of V.E. Day and another chance to reflect on how I have something wrong with my brain…

I always feel like these around these big commemorations. The fact that World War 2 lasted about six years means that there’s always another landmark divisible by 5 around the corner. If we’re not marking the Battle of Britain, it’s D. Day or Dunkirk or V-J Day or, in the years between, the start or end of World War I. I know part of my problem comes down to low-level autism or Asperger’s. I can’t get excited by things that don’t excite me but, more worryingly, I also lack the capacity to bluff. I say exactly how I feel and that makes people get cross with me. I’ve endured it all my life. “Oh, David! Why can’t you enjoy yourself? Why do you have to be so difficult and spoil it for everybody?”

To some, my inability to treat today’s commemorations with the “respect they deserve” means that I’m everything from an unpatriotic arsehole to a sneering intellectual. I might be a bit of both but, like so many things, it’s more complicated than that.

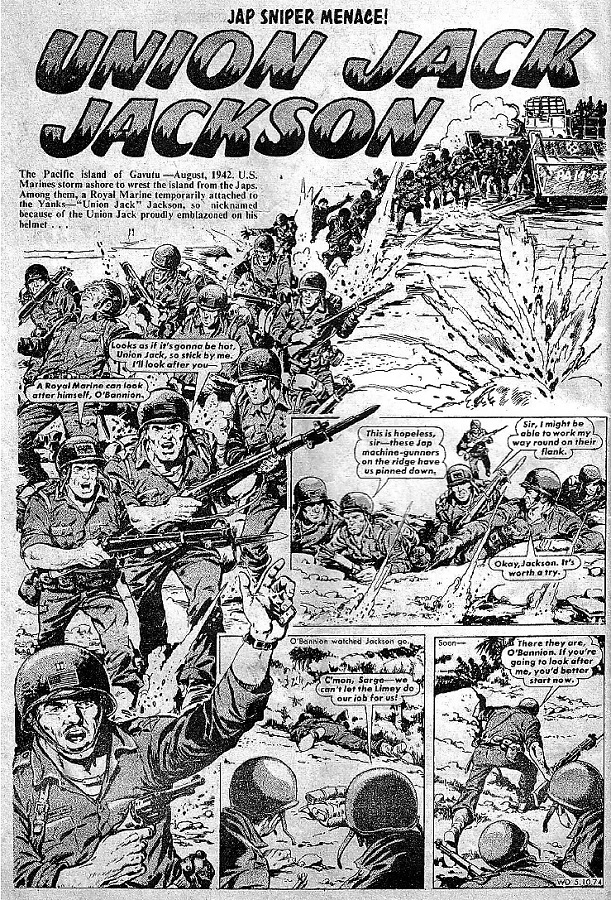

Like most lads my age, I was brought up to have great reverence towards the British Army. I had an Action Man, complete with gripping hands, and my favourite book/magazine of my early years was Warlord published by DC Thompson. It was filled with cartoon strips which prided themselves on being more realistic than the usual war story. The reality, however, was that the jingoism was turned way up to 11. With hindsight, some of what I read was shamelessly racist but I was a very young kid and those were very different days…

Yet as I grew up, I started to read history and I began to notice that reality didn’t match my comic books. Even popular culture was giving me different messages. Take the film, The Great Escape. It’s always been one of my favourites yet a film that ultimately pains me. It’s a favourite because who doesn’t love Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough, and Charles Bronson being in the same movie? I also love it because I adore anything about engineering problems. My favourite bits are when they move the stove and fix the chimney with a short extension tube. I love the solution to hiding soil. I love the forgery bits and, of course, I love the digging.

It pains me, though, because of the ending. [Spoiler alert] I hate how it ends with nearly everybody being executed by the Germans. It doesn’t conform to my narrative expectations. How can it be the “great escape” if hardly anybody escapes? Another absolutely favourite is Where Eagles Dare, which ends properly, with the heroes victorious. Yet I also understand how The Great Escape is doing the decent thing. It ends up as quite a profound statement about war. It undercuts my expectations and that is also what I understand about war. Very little about our Victory in Europe was black and white; there were more defeats than victories. I reviewed Max Hasting’s new book, The Dam Busters, a few weeks ago and noted the fact that he undercuts the myth. A remarkable engineering achievement, undoubtedly, and conspicuous by the bravery of the airmen. Yet historians struggle to declare it a victory or to justify the loss of life (especially of innocents killed by the floodwaters). In my life, World War Two has always had that doubleness.

My dad was a psychiatric nurse in a local hospital and throughout my childhood, I would occasionally go with him to visit his ward. It was the usual stuff of life – dropping things off, picking things up, signing paperwork – but it wasn’t usual for a young boy. He specialised in geriatric care and the wards in those days were filled by old men, many of whom had served in World War 2. My dad probably didn’t think much about it – he also had a great capacity to be coldly rational about things – but I know in my adulthood how much those visits scarred me. Many of these men still carried their injuries; faces that had been blown apart or large portions of their skull flattened. Like some people have nightmares about spiders, I still have nightmares about facial deformity. Any horror based around World War 2, the Nazis, and medical experimentation freak me out.

I can’t think about the Battle of Britain without thinking of those men. I first saw the film The Battle of Britain in the hospital cinema; an unsettling evening since the film clearly triggered emotions in some of those men who were escorted from the hall. I never saw another film there. Even my dad probably thought it was a bit too much.

I feel huge compassion and sadness for those men who passed their final years in those wards. I also think about my maternal granddad, who was one of my favourite people. I always thought his hearing aids were a sign of his advanced age but he’d lost his hearing as a young man, serving as a gunner in the trenches of World War I from 1915 to 1918. He never marked any commemoration. Never wore a poppy. Never really spoke about it.

So, every time I find myself looking at the nation marking one of these occasions, I find myself today wondering what people are celebrating and even if the word commemoration is too often confused with celebration. I’m not one of those people ashamed at what Britain did during the war but I am ashamed at how we treated some of our soldiers who came home. I feel distinct unease that this particular commemoration comes at a time when our front-line NHS staff have been so shamefully let down by our government. How will we look back in 75 years on our Victory against Coronavirus? I hope we’ll remember the sacrifices being made but also their shameful treatment at the hands of the state. I hope we remember that victories are often bittersweet.

I particularly dislike what so many of these commemorations have become. There is surely no coincidence that Nigel Farage chose this week to go to Dover where he stood on the cliffs and complained about migrants. I want to commemorate Victory in Europe, certainly, but not what the Daily Mail this week described as “Victory Over Europe” when peddling some worthless coin. My neighbours have erected a large flag on the front of the house. It’s not the Union Flag, though, but the England flag with four lions. So, V.E. Day is also predictably tinged with a bit of English Nationalism…

The rejoinder to the above is that I’m thinking too much. V.E. Day is about marking the sacrifices made by a generation in retaining our freedoms. Remember only that and mark it with respect. All the other matters we can leave for another day. Except, I think if today means anything, it should be about thinking too much. I will mark it in my usual complicated way of trying to discern the reality from the jingoism, the truths from the momentary fads. I won’t be waving flags or singing on the doorstep, but I will do something. For a start, I will write this little tribute. And who can tell me that this isn’t closer to the meaning of today?

@DavidWaywell

I agree with every word. I’ve been pondering the difference between celebration and commemoration myself. As an aside. I gather from your comments you now want us to share post. Can you give us a short cut?

Ah, thanks Max. Such a good suggestion. I clearly lack a social media share button. Leave it with me! I’m onto it!

Regarding the blurring, I commented on Twitter that I think WW2 has become too ingrained in our national psyche. Before WW2, we were witnessing the end of Empire and the healthy process would have been seen that through, grow more mature as a nation, and emerge with a new vibrancy. Instead, victory in Europe gave that old psychology a bit of a boost. Instead of thinking we rule the world, we become the world’s liberators and British ingenuity was like no other. It’s such a dangerous narrative that doesn’t make us stronger. It’s why I was worried that the government seemed to be treating coronavirus a bit like Enigma; a problem only the British could crack because our modelling was the best. Sadly, it wasn’t.

I constantly wonder about Germany. They lost so they don’t have a chance to ‘celebrate’. Losing changed them for the better. We won but we didn’t address our national weaknesses. We’re still a nation run out of London by a narrow elite, believing our myths and silly cultural tropes. Can’t be good for us.